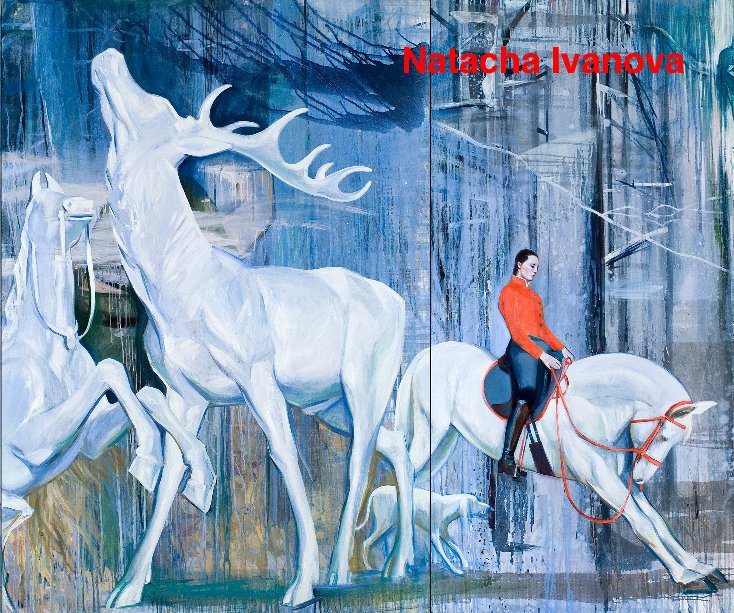

Natacha Ivanova

The Deer Hunter

von CUETOPROJECT

Dies ist der Preis, den Ihre Kunden sehen. Listenpreis bearbeiten

Über das Buch

NATACHA IVANOVA: ICONS OF DIANA THE HUNTRESS

Cueto Project has the pleasure to announce the first American solo show of

Natacha Ivanova

Opening Thursday September 4th, reception from 5 to 8 pm

Exhibition from September 5th until October 25th

The artist is special type, an eccentric persona originating from a foreign

universe. Their quest is to recreate for the inhabitants of this world a semblance

of the magnificence and oddity that characterize the realm from which they are

derived. In so doing, the best of these artist types generate something

mysteriously intriguing and yet simultaneously familiar. Natacha Ivanova’s world,

reproduced on the canvas screen, captures the viewer in just this way; it is

engrossing like a dream, bewitching like a dark forest that engulfs any visitor,

mischievous like a message whose meaning is given then instantly retracted.

While her visions and messages are as fresh as the new day, her formula is an

age-old one: a canvas and some oil paint, the scent of turpentine filling the studio

with proverbial aromas, a tall easel resembling a torture pole, brushes aimed at

the subject like so many arrows, silence then laughter, countless sharp glances

weighing up the model and turning life into a two-dimensional story. In complete

control of this metamorphosis is the apparent descendant of Diana the huntress

herself, Slav-blonde, with a spirit as free and as air. The studio is her realm. Her

virtuoso warrior hands master paint like sound alchemy.

Her paintings often resemble the style of Gustave Moreau and frequently

perpetuate a theme throughout a number of canvases. They veil in melancholy

the faces love and loss, waking dreams that bring simultaneous shudders of

desire and dread, and fleeting visions that sum up the feeling of being alive. The

blue of cold seas might be her banner: “Blue is the value of something absolute

and eternal. It’s the strongest of spiritual experiences… Like all little things, in the

end of the day,” confesses Natacha the Russian, solemn behind her porcelain

beauty. “I was painting on an island in Normandy, cut off from the world by the

high tide, for a landscape competition on a theme. For several days an incredible

storm lashed the island. It was impossible to paint, so fierce was the gale. Icy

spring. It was so cold that I covered myself with everything I could lay my hands

on, including the bed sheets, like a refugee. And the din died down. A huge

2

silence. The sun. And I suddenly saw a white dove appear, my heart was beating

so fast, I’m quite sure that divine dove was my beloved sister”. In Natacha

Ivanova’s canvases, birds fly over human beings like ancient messengers: white

owls fly through nights above and around sleeping beauties with great manes of

hair (Dangerous Sleeping Partners, 2007). These birds are like sentinels of the

forest, a place of adventure and childhood (Wonderland, 2006); they replace the

scepter of Artemis and sovereigns of yore (Maria, 2007). “Owls are the old-

fashioned go-betweens, between the world of the quick and the dead. Like

dreams, they bring us messages from somewhere else by way of symbols which

nurture us, sum us up, and move us”, explains the painter, who has been

fascinated with symbols and their integration into her works from a very young

age. At times, there is an erotic undertone, as with (Black Virgin II, 2006): veiled

by the melancholy of night, a bird pulls from the breast of a woman in mourning a

bizarre substance, soft and pink like a flower.

In, Swans (2008), the bird is specifically engendered male, a direct reference to

Leda and the swan: “The swan, so obviously male, is a twofold creature,

incredible for its beauty and its cruelty. I like this combination of opposites that

saves us from boredom”, says this native of St. Petersburg (1975), a child artist

trained at the Hermitage school, French by adoption for the past ten years, and a

timeless acrobat of painting. Interestingly, all the women Natacha paints—

beautiful, dangerous, pseudo-calm and headstrong— seem to have something of

the swan about them, that mythological hero of enshrouded seduction. In her

amazing triptych with more than forty women dressed up as nurses (Nurses,

2008), the faces have that distant family likeness kissed by the ideal, and yet

each one looks like their model: the bruised child beneath the triumph of round-

bosomed Venus, the sovereign mother like a Nordic queen, the delicate soul of

the aesthete beneath the pretty little face straight from the Middle Ages, the

primitive vitality of the Tahitian woman with her black head of hair, the woman

weeping tearlessly, the red-headed dominatrix with her fearless, irreproachable

eyes, the voluptuous lady looking elsewhere, the brazen woman playing with her

profile on the canvas, as huge as a theatre… Each woman is a real portrait,

captured live, a lengthy process combining analysis and light, painting and

alchemy of encounter. Each new portrait alters the picture’s rhythm, and renders

the whole thing devilishly demanding, magical, and dynamic in its presence.

Some seventy women posed for many long hours in the studio in old Paris.

Being the fearsome judge that she is, Natacha decided to remove almost thirty of

them, “to keep just the most alive, the most personal, and the most beautiful.”

Beneath the white headgear any idea of artifice dissipates. Neither jewels nor

ornaments, nor dazzling smiles of conquistador women, nor frivolous décolletés

of dreamy, languid seductresses exists on these three panels. “I deal with the

faces in this monumental fresco like nudes. Each one must vibrate, as if she

were appearing to you of her own accord in flesh and blood. Their [apparent]

identity as nurses is more a symbol than a function, a reference to sacrifice and

3

eroticism, to the gift and its mystery. When I painted the diptych of the soldiers

[referring to The Soldiers, 2007], I didn’t want to get interested in military figures,

but rather in combatants in the metaphorical sense.” Butterflies and stags, night

and the morning bird, all have come to mingle with the uniforms in a thoroughly

symbolist union in this work. But beware: the nature of legends is stalking you!

Animals invade the frame and chimaeras have their natural place therein: a red

horse, strange denizen of treetops, large as a fire dragon, a giant white rabbit

running out of the frame like a unicorn, “symbols of might and purity”- Natacha

Ivanova confesses “I like the unicorn for its powerful symbolism. That single horn

is a spiritual arrow, the sun’s ray, God’s sword. It incarnates the penetration of

the divine in the creature and represents the Virgin impregnated by the Holy

Ghost in Christian iconography. This single horn can symbolize a stage on the

path from differentiation and biological creation to psychic development and

sexual sublimation. This is a fine allegory of art, too.” This young contemporary

artist is as solidly moored in her day and age as she is in the history of art, from

the famous Unicorn Tapestry in the Cluny Museum, Paris, to the rooms of

ancient sculptures in the Hermitage, St. Petersburg. Natacha Ivanova is the

daughter of two Russian artists from St. Petersburg. Olga, the brunette, with

remote Greek origins, and Alexei, man from the North, fair-haired as a Viking.

The combination of these two artistic temperaments, pulsing through her veins,

pushed Natacha innately to take up paper and pencil, hanging her drawings from

early childhood in many a temporary show, and in so doing stimulating her mind

and carving out for herself a niche of freedom.

This drive for freedom of mind and expression is presented in codes of color on

the vibrant canvases of Natacha Ivanova. Red is there, roaring with the energy

of a flame; it is the red dream of desire, deep red like “hell, blood, life, rebirth” in

three self-portraits of a wild, almost ferocious sensuality (Diane and Actaeon,

2005). Green brings everything back to life after the Russian winter, and poisons

like the spells from stills. The green dream of spring with the secret kiss to the

wolf, instinct freed, foe become friend. “Traditionally, the wolf is synonymous with

danger. In Russian tales, it may also help the hero carry out his task. Evil ending

up as good. It is also, to my eye, the outward expression of the hidden side of the

personality, savage, instinctive, spontaneous”. In the second panel of this

melancholic diptych, which both moves and fascinates, the dream is a sick,

mortal green. It is the “duel with oneself, the sacrifice inherent in love, self-

sacrifice in order to receive the other” (Love, 2004). All painters have their own

language. Natacha’s has Russian roots, mystic like a hidden church, unspoken,

but louder than all the State’s bans.

“As a painter and restorer of old paintings, my mother started painting icons in

France in a small monastery at Meudon. Everything in them is coded, the colors,

the composition, the figures, the gestures. Nothing is left to chance. When you

copy them, you understand them intimately. The way you understand faith in and

4

fear of God when, as a penitent, you climb the tall steps of orthodox cathedrals.

Then wonderment ensues, and adoration in the strongest sense of the term. My

favorite icon is the Madonna with Child, even if the small, old person’s face of the

Child-King horrified me like something weird, and frightened me. In my personal

Middle Ages, I have doubts, and I’m always afraid of a God who punishes”,

admits this young woman, moved by the forest and its spells, the beauty of

women, the naked power of Zeus. “As a child, my father would take me on his

knees to get me to draw, guiding my hand. He was a sun. I became a follower of

the sun. As a painter, he really wanted me to like Rembrandt. But I preferred the

heroes of mythology and the statue of Zeus in the Hermitage, powerful and

naked like a human being and an absolute leader surrounded by nymphs”.

Natacha, a sensitive soul, has a different take on the melancholy portraits of El

Greco, which show you the person behind the black-clad court Caballero beneath

the rigid ruff, the brilliant wildness of Goya and the prints of lowly folk by

Rembrandt “where the angels flying away have the dirty feet of the beggar.”

Text by Valérie Duponchelle

Translated by Simon Pleasance and Caitlin Boucher

Cueto Project has the pleasure to announce the first American solo show of

Natacha Ivanova

Opening Thursday September 4th, reception from 5 to 8 pm

Exhibition from September 5th until October 25th

The artist is special type, an eccentric persona originating from a foreign

universe. Their quest is to recreate for the inhabitants of this world a semblance

of the magnificence and oddity that characterize the realm from which they are

derived. In so doing, the best of these artist types generate something

mysteriously intriguing and yet simultaneously familiar. Natacha Ivanova’s world,

reproduced on the canvas screen, captures the viewer in just this way; it is

engrossing like a dream, bewitching like a dark forest that engulfs any visitor,

mischievous like a message whose meaning is given then instantly retracted.

While her visions and messages are as fresh as the new day, her formula is an

age-old one: a canvas and some oil paint, the scent of turpentine filling the studio

with proverbial aromas, a tall easel resembling a torture pole, brushes aimed at

the subject like so many arrows, silence then laughter, countless sharp glances

weighing up the model and turning life into a two-dimensional story. In complete

control of this metamorphosis is the apparent descendant of Diana the huntress

herself, Slav-blonde, with a spirit as free and as air. The studio is her realm. Her

virtuoso warrior hands master paint like sound alchemy.

Her paintings often resemble the style of Gustave Moreau and frequently

perpetuate a theme throughout a number of canvases. They veil in melancholy

the faces love and loss, waking dreams that bring simultaneous shudders of

desire and dread, and fleeting visions that sum up the feeling of being alive. The

blue of cold seas might be her banner: “Blue is the value of something absolute

and eternal. It’s the strongest of spiritual experiences… Like all little things, in the

end of the day,” confesses Natacha the Russian, solemn behind her porcelain

beauty. “I was painting on an island in Normandy, cut off from the world by the

high tide, for a landscape competition on a theme. For several days an incredible

storm lashed the island. It was impossible to paint, so fierce was the gale. Icy

spring. It was so cold that I covered myself with everything I could lay my hands

on, including the bed sheets, like a refugee. And the din died down. A huge

2

silence. The sun. And I suddenly saw a white dove appear, my heart was beating

so fast, I’m quite sure that divine dove was my beloved sister”. In Natacha

Ivanova’s canvases, birds fly over human beings like ancient messengers: white

owls fly through nights above and around sleeping beauties with great manes of

hair (Dangerous Sleeping Partners, 2007). These birds are like sentinels of the

forest, a place of adventure and childhood (Wonderland, 2006); they replace the

scepter of Artemis and sovereigns of yore (Maria, 2007). “Owls are the old-

fashioned go-betweens, between the world of the quick and the dead. Like

dreams, they bring us messages from somewhere else by way of symbols which

nurture us, sum us up, and move us”, explains the painter, who has been

fascinated with symbols and their integration into her works from a very young

age. At times, there is an erotic undertone, as with (Black Virgin II, 2006): veiled

by the melancholy of night, a bird pulls from the breast of a woman in mourning a

bizarre substance, soft and pink like a flower.

In, Swans (2008), the bird is specifically engendered male, a direct reference to

Leda and the swan: “The swan, so obviously male, is a twofold creature,

incredible for its beauty and its cruelty. I like this combination of opposites that

saves us from boredom”, says this native of St. Petersburg (1975), a child artist

trained at the Hermitage school, French by adoption for the past ten years, and a

timeless acrobat of painting. Interestingly, all the women Natacha paints—

beautiful, dangerous, pseudo-calm and headstrong— seem to have something of

the swan about them, that mythological hero of enshrouded seduction. In her

amazing triptych with more than forty women dressed up as nurses (Nurses,

2008), the faces have that distant family likeness kissed by the ideal, and yet

each one looks like their model: the bruised child beneath the triumph of round-

bosomed Venus, the sovereign mother like a Nordic queen, the delicate soul of

the aesthete beneath the pretty little face straight from the Middle Ages, the

primitive vitality of the Tahitian woman with her black head of hair, the woman

weeping tearlessly, the red-headed dominatrix with her fearless, irreproachable

eyes, the voluptuous lady looking elsewhere, the brazen woman playing with her

profile on the canvas, as huge as a theatre… Each woman is a real portrait,

captured live, a lengthy process combining analysis and light, painting and

alchemy of encounter. Each new portrait alters the picture’s rhythm, and renders

the whole thing devilishly demanding, magical, and dynamic in its presence.

Some seventy women posed for many long hours in the studio in old Paris.

Being the fearsome judge that she is, Natacha decided to remove almost thirty of

them, “to keep just the most alive, the most personal, and the most beautiful.”

Beneath the white headgear any idea of artifice dissipates. Neither jewels nor

ornaments, nor dazzling smiles of conquistador women, nor frivolous décolletés

of dreamy, languid seductresses exists on these three panels. “I deal with the

faces in this monumental fresco like nudes. Each one must vibrate, as if she

were appearing to you of her own accord in flesh and blood. Their [apparent]

identity as nurses is more a symbol than a function, a reference to sacrifice and

3

eroticism, to the gift and its mystery. When I painted the diptych of the soldiers

[referring to The Soldiers, 2007], I didn’t want to get interested in military figures,

but rather in combatants in the metaphorical sense.” Butterflies and stags, night

and the morning bird, all have come to mingle with the uniforms in a thoroughly

symbolist union in this work. But beware: the nature of legends is stalking you!

Animals invade the frame and chimaeras have their natural place therein: a red

horse, strange denizen of treetops, large as a fire dragon, a giant white rabbit

running out of the frame like a unicorn, “symbols of might and purity”- Natacha

Ivanova confesses “I like the unicorn for its powerful symbolism. That single horn

is a spiritual arrow, the sun’s ray, God’s sword. It incarnates the penetration of

the divine in the creature and represents the Virgin impregnated by the Holy

Ghost in Christian iconography. This single horn can symbolize a stage on the

path from differentiation and biological creation to psychic development and

sexual sublimation. This is a fine allegory of art, too.” This young contemporary

artist is as solidly moored in her day and age as she is in the history of art, from

the famous Unicorn Tapestry in the Cluny Museum, Paris, to the rooms of

ancient sculptures in the Hermitage, St. Petersburg. Natacha Ivanova is the

daughter of two Russian artists from St. Petersburg. Olga, the brunette, with

remote Greek origins, and Alexei, man from the North, fair-haired as a Viking.

The combination of these two artistic temperaments, pulsing through her veins,

pushed Natacha innately to take up paper and pencil, hanging her drawings from

early childhood in many a temporary show, and in so doing stimulating her mind

and carving out for herself a niche of freedom.

This drive for freedom of mind and expression is presented in codes of color on

the vibrant canvases of Natacha Ivanova. Red is there, roaring with the energy

of a flame; it is the red dream of desire, deep red like “hell, blood, life, rebirth” in

three self-portraits of a wild, almost ferocious sensuality (Diane and Actaeon,

2005). Green brings everything back to life after the Russian winter, and poisons

like the spells from stills. The green dream of spring with the secret kiss to the

wolf, instinct freed, foe become friend. “Traditionally, the wolf is synonymous with

danger. In Russian tales, it may also help the hero carry out his task. Evil ending

up as good. It is also, to my eye, the outward expression of the hidden side of the

personality, savage, instinctive, spontaneous”. In the second panel of this

melancholic diptych, which both moves and fascinates, the dream is a sick,

mortal green. It is the “duel with oneself, the sacrifice inherent in love, self-

sacrifice in order to receive the other” (Love, 2004). All painters have their own

language. Natacha’s has Russian roots, mystic like a hidden church, unspoken,

but louder than all the State’s bans.

“As a painter and restorer of old paintings, my mother started painting icons in

France in a small monastery at Meudon. Everything in them is coded, the colors,

the composition, the figures, the gestures. Nothing is left to chance. When you

copy them, you understand them intimately. The way you understand faith in and

4

fear of God when, as a penitent, you climb the tall steps of orthodox cathedrals.

Then wonderment ensues, and adoration in the strongest sense of the term. My

favorite icon is the Madonna with Child, even if the small, old person’s face of the

Child-King horrified me like something weird, and frightened me. In my personal

Middle Ages, I have doubts, and I’m always afraid of a God who punishes”,

admits this young woman, moved by the forest and its spells, the beauty of

women, the naked power of Zeus. “As a child, my father would take me on his

knees to get me to draw, guiding my hand. He was a sun. I became a follower of

the sun. As a painter, he really wanted me to like Rembrandt. But I preferred the

heroes of mythology and the statue of Zeus in the Hermitage, powerful and

naked like a human being and an absolute leader surrounded by nymphs”.

Natacha, a sensitive soul, has a different take on the melancholy portraits of El

Greco, which show you the person behind the black-clad court Caballero beneath

the rigid ruff, the brilliant wildness of Goya and the prints of lowly folk by

Rembrandt “where the angels flying away have the dirty feet of the beggar.”

Text by Valérie Duponchelle

Translated by Simon Pleasance and Caitlin Boucher

Eigenschaften und Details

- Hauptkategorie: Kunst & Fotografie

-

Projektoption: Standard-Querformat, 25×20 cm

Seitenanzahl: 40 - Veröffentlichungsdatum: Sept. 07, 2008

- Schlüsselwörter Russian, Painter, Contemporary

Mehr anzeigen